Glycogen as Energy Reserve: Storage Capacity and Use

Understanding glycogen synthesis, storage capacity, mobilization during fasting and exercise, and physiological regulation of this critical energy reserve.

Introduction

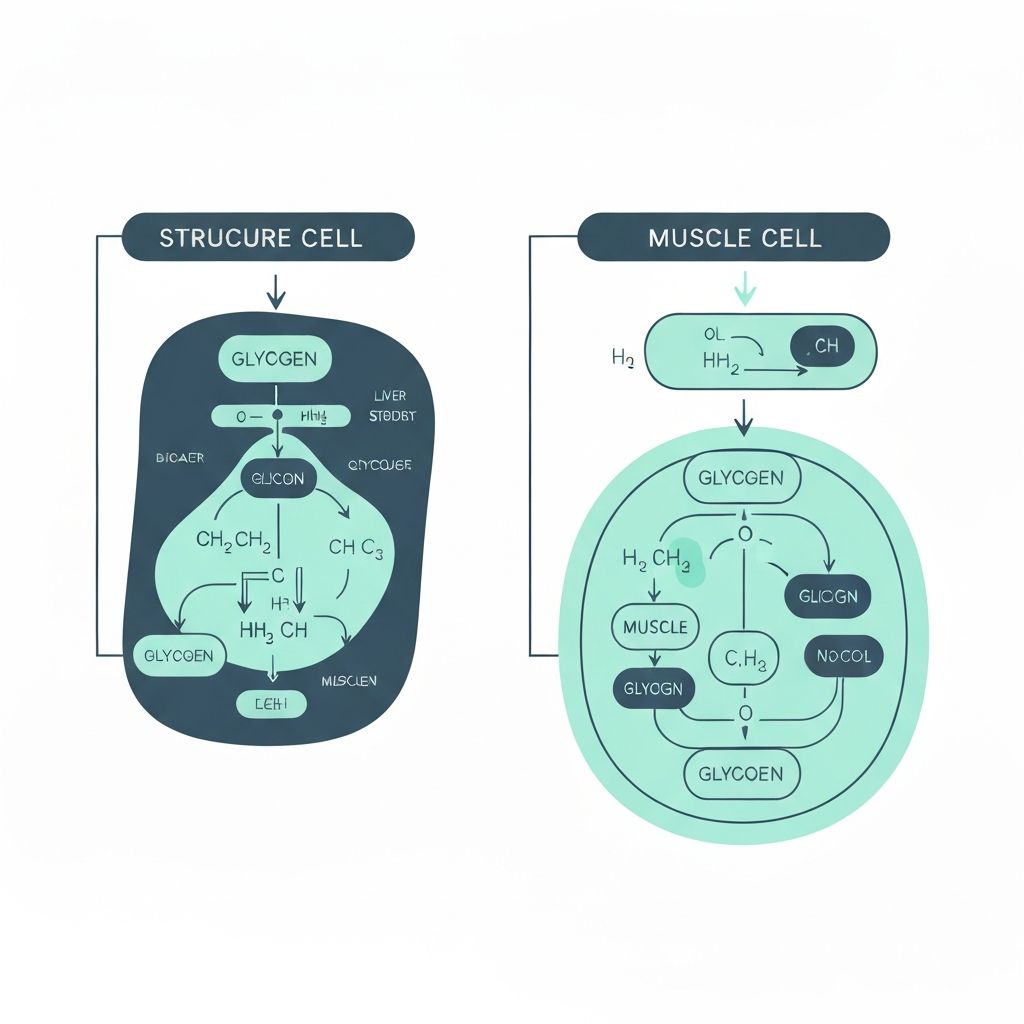

Glycogen is the branched-chain polymer of glucose that serves as the primary carbohydrate storage form in animals. Stored in the liver and skeletal muscle, glycogen represents an immediate energy reserve that can be rapidly mobilized when blood glucose drops or when energy demands increase during physical activity. This article explores glycogen synthesis, storage capacity, mobilization mechanisms, and physiological significance.

Glycogen Structure

Glycogen is composed of glucose units linked together in a highly branched structure. The primary linkage is alpha-1,4 glycosidic bonds connecting glucose molecules linearly; branch points occurring every 8-12 residues involve alpha-1,6 glycosidic bonds. This branched architecture serves two functions: it increases the solubility of this large polymer, and it provides numerous terminal glucose units available for rapid mobilization without requiring enzymatic degradation of the entire molecule.

Hepatic Glycogen Storage

The liver stores approximately 100-120 grams of glycogen under normal fed conditions. This hepatic glycogen pool serves a specific function: maintaining blood glucose during fasting periods. During the postabsorptive state (4-6 hours after eating), declining insulin and rising glucagon trigger hepatic glycogenolysis—the breakdown of glycogen to glucose-1-phosphate, which is converted to free glucose and released into the bloodstream.

Hepatic glucose release from glycogen maintains blood glucose between 70-100 mg/dL during fasting. Hepatic glycogen is typically depleted after 12-24 hours of fasting; thereafter, glucose is maintained through gluconeogenesis from amino acids, lactate, and glycerol.

Muscle Glycogen Storage

Skeletal muscle contains 400-500 grams of glycogen, depending on muscle mass and training status. Unlike hepatic glycogen, which is released as glucose into the blood, muscle glycogen is stored and utilized entirely within muscle cells. During muscle contraction, glycogen is broken down and glucose-6-phosphate enters glycolysis, providing ATP for muscle work.

Muscle glycogen availability is a limiting factor for endurance exercise performance. High-intensity exercise lasting longer than 60-90 minutes becomes increasingly dependent on muscle glycogen availability. Athletes exploit this through "glycogen loading"—consuming high-carbohydrate diets in the days before competition to maximize muscle glycogen stores.

Glycogenesis: Synthesis and Storage

Glycogenesis is the metabolic pathway that synthesizes glycogen from glucose. After a meal, when blood glucose and insulin are elevated, glucose-6-phosphate (from glucose uptake and initial phosphorylation) is converted through a series of enzymatic steps to UDP-glucose, the activated glucose unit. The enzyme glycogen synthase, activated by insulin, catalyzes the addition of glucose units to the growing glycogen chain.

Glycogen synthesis is most active when insulin is elevated (fed state), glucose is abundant, and energy status is favorable. The branching enzyme creates the alpha-1,6 branch points, which is essential for the highly branched structure that enables rapid glucose mobilization when needed.

Glycogenolysis: Mobilization

Glycogenolysis breaks glycogen down to glucose units available for energy. The enzyme glycogen phosphorylase, activated by the hormones glucagon and epinephrine (adrenaline), catalyzes the breaking of alpha-1,4 bonds, releasing glucose-1-phosphate units. The branching structure of glycogen is functionally significant here: the numerous branch points provide multiple sites for simultaneous enzyme action, enabling rapid mobilization when energy demand suddenly increases.

In the liver, glucose-1-phosphate is converted to free glucose and released into blood. In muscle, glucose-6-phosphate (the product of glucose-1-phosphate conversion) cannot be converted to free glucose (due to lack of glucose-6-phosphatase enzyme in muscle), so it enters glycolysis directly as fuel for muscle contraction.

Regulation of Glycogen Metabolism

Glycogen metabolism is exquisitely regulated through multiple mechanisms. Insulin promotes glycogenesis and inhibits glycogenolysis—storing glucose when it is abundant. Glucagon and epinephrine promote glycogenolysis and inhibit glycogenesis—mobilizing glucose when energy is needed. Glycogen phosphorylase kinase, activated by calcium release during muscle contraction, stimulates glycogenolysis even before hormonal signals arrive, enabling rapid response to physical demand.

Energy status also provides direct feedback: when AMP (indicating low energy) is elevated, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) enhances glycogenolysis, while high ATP inhibits glycogenolysis. This elegant system ensures glucose is stored when abundant and released when needed.

Physiological Significance

Glycogen storage provides rapid, immediate glucose availability without requiring digestion of new food or hepatic glucose synthesis. During brief, intense exercise, muscle glycogen is the primary fuel. During prolonged exercise or fasting, hepatic glycogen maintains blood glucose to support the central nervous system and red blood cells, which depend heavily on glucose. This buffering capacity is critical for survival during periods without food intake and for supporting high-intensity physical performance.

Glycogen and Body Weight

Glycogen storage accounts for substantial water weight in the body—each gram of glycogen binds approximately 3-4 grams of water. Rapid changes in body weight often reflect glycogen and associated water changes rather than tissue mass changes. Depletion of glycogen stores (through extended fasting or very low-carbohydrate diets) produces rapid weight loss largely from water loss, while glycogen repletion through carbohydrate reintroduction rapidly restores this water weight.

Conclusion

Glycogen functions as a critical intermediate-term energy reserve, bridging the gap between dietary carbohydrate availability and the need for constant glucose supply to tissues. Its storage capacity, rapid mobilization, and sophisticated regulation enable both immediate energy provision during physical activity and sustained blood glucose maintenance during fasting. Glycogen metabolism represents a fundamental adaptive system supporting human survival and performance.